By Bryan Hess and Sarah Schaeffer –

“There is no time to blame only time to grow and learn from what you done wrong.”

These are the words of 32-year-old Anthony Rashan Lewis. Fifteen years ago, at the age of 17, he was convicted of murder in the second degree after a robbery in Lancaster, Pa. ended in the death of the convenience store clerk. Lewis didn’t plan the shooting, obtain the weapon or pull the trigger. Nevertheless, Lewis will be in prison for the rest of his life, just like 472 other juveniles in Pennsylvania – the most of any state in the United States, say criminal experts. It’s also more than in any country anywhere in the entire world.

Charging juveniles as adults and putting many of them away in state prisons for the rest of their lives is not without controversy even within Pennsylvania which leads the universe with this dubious distinction. Should these youths, some as young as 11, be given a second chance or will they forever be a threat to society?

Should society attempt a risky rehabilitation or lock them up and throw away the key?

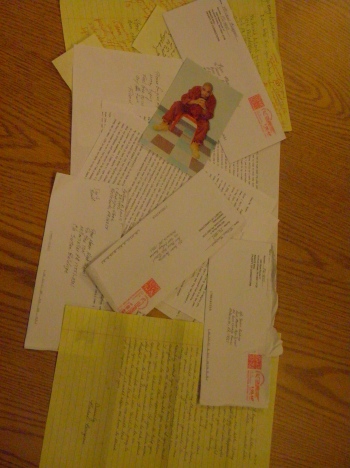

For this report, Penn Points contacted and maintained written correspondence with several juveniles who were charged as adults for their crimes and who are serving a life sentence in adult correctional facilities in Pennsylvania. Excerpts from that correspondence appear in this story exactly as the inmates wrote. No changes were made to correct grammar or punctuation. The decision was made to let the young men tell their stories in their own voice.

“I dropped out of school 3 days into my Senior Year of High School. So with so much free time we just kept on finding ways to get money like burglaries and armed robberies and car thefts. These things eventually led up to what I’m really incarcerated for, a double homicide. So all of these things that I thought was fun and exciting, really wasn’t,” wrote 27-year-old Michael Bourgeois, another juvenile “lifer.”

“As an adult we know how to make the right decisions as a juvenile we struggle about what is the right decision to make, especially when it comes from peer pressure and drugs,” wrote Lewis, now 32 years old, from Rockview Correctional Institution, located in the mountains of Centre County, Pa.

Lewis certainly didn’t make the right decision t he night he agreed with a group of boys he had been hanging out with that a robbery would be a good way to get the money to score some marijuana.

Because one convenience store did not appear to have security cameras, it became the target. The clerk, 38-year-old Michael Heath, was shot in the neck by one of the boys and bled to death while on the phone with police dispatchers. He left behind a wife and son.

After Lewis’ trial and his second-degree murder conviction, some jurors said they were surprised that the youths could be sentenced to life in prison without possibility of parole. The judge had not informed them of the mandatory sentence connected to the conviction of youths charged as adults for second-degree murder in Pennsylvania.

Even so, jurors cited the premeditation of the act, the fact the boys had gone home to get hooded sweatshirts to wear and gloves, made them clear accomplices whether they were in the store during the murder or lookouts outside. They were unmoved during the trial when defense attorneys brought up the defendants low IQs.

“I was high that day and night but I just met most of my co-defendant’s who I was arrested with that next day,” recalled Lewis, “On the night of may 23, 1996, I was out with some friends and one them came up with a plan to rob someone or a place, like a store, well two of them made the plan inside one of my co-defendant house and came out and told all of us about the plan. I was to high to walk away from them so I stayed there, clueless, and didn’t care. Well that night it was getting chilly so I went home to get a sweatshirt, but the only one I had was the one that my friend give me to hold so I put it on and before I left my house I ask my Aunt for some money and took my medication, I was on.and left back to my co-defendant house. Well later that night we was driven to a street behind a store and that when thing’s took the wrong turn, and it’s funny because I was told be them to check out the store, and report back to them as I did, and I was told to be a look out, outside the store. And than I heard a gun shot inside the store, my co-defendant had shot the guy who was working inside the store. Everyone started to run, I was stuck for a few minutes and ran with them out of fear,” wrote Lewis.

It was just this type of juvenile crime that the Pennsylvania Legislature and other legislatures across t he country were trying to address when they passed Pa. Act 33 in 1995.

Crime, including juvenile crime, had spiked nationwide in the late 1980s and early 1990s. By 1993, the annual FBI reports showed the murder arrest for every 100,000 juveniles in the country was 14.4 percent, an all-time high. By comparison, that rate was halved by 2004 and has continued to decline to its lowest point in 2008.

But the increase in juvenile crime in the 1990s prompted legislators to amend the Juvenile Crime Code in Pennsylvania to exclude automatically from the juvenile system any youths who fit the following criteria at the time of the crime:

-The youth was 15 years or older at the time of the alleged crime.

-The youth was charged with rape; involuntary deviate sexual intercourse; aggravated assault; robbery; robbery of a motor vehicle; aggravated indecent assault; kidnapping; voluntary manslaughter; or an attempt, conspiracy, or solicitation to commit murder or any of the crimes listed.

-The youth used a deadly weapon during commission of the crime.

When these factors are present, district attorneys around the state have no choice but to follow the law and charge the juvenile offenders as adults.

But there are many other cases, where gray areas make the decision more complicated.

Any youths who have been charged as an adult but who want to be “decertified” and tried as juveniles must have their attorney request a decertification hearing to return the case to juvenile court.

During those hearings, many different aspects of the juvenile are examined. The first one, and the one that is normally the deciding factor, said many experts, is if the juvenile will be able to respond to treatment that is offered in the juvenile system.

Treatment is not as common once the juvenile enters the adult system. Prior criminal history, age of the juvenile, how much injury was caused and the reaction of the juvenile to the crime they committed are other factors that play into the decision of whether or not a juvenile will be tried as an adult. However, if charged with any degree of murder in Pennsylvania or the other violent crimes that the amended statute names, the case is automatically sent to adult court.

The argument continues within the state whether or not juveniles are capable of making decisions that can and will affect them for the remainder of their life? And if so, is sentencing a juvenile to life without parole a fair punishment?

Pennsylvania has by far the lion’s share of the 2,500-some juveniles with life sentences in the United States, called by some “the other death sentence” because they will die in prison. Although far larger in population, California has about 250 inmates who were juveniles when they were given their life sentences. Texas has only four juveniles serving life sentences.

The concept of sentencing juveniles to life is not universally accepted. Thirteen states prohibit the practice entirely of mandatory life sentences for juveniles. The rest of the world agrees.

When the United Nations drafted a resolution banning the practice of sentencing youths to life in prison in December of 1990, only two countries in the world refused to sign it – the United States and Somalia. However records show there may be as few as 12 juveniles in jail without parole possibilities in the rest of the world, not counting the U.S.

Although the practice does ensure that the particular youth will not be able to get out and recommit a crime, there seems to be no correlation between the life sentence and crime prevention. States that do not have the practice of sentencing juveniles to life often have lower juvenile crime rates, even violent juvenile crime rates, than states who do.

Some experts believe there is a definite physical and emotional difference between juveniles and adults.

According to Jerome Gottlieb, a forensic psychiatrist for over 30 years, the brain is not fully developed until sometime in the 20s. The last part of the brain to develop, Gottlieb said, is the part that regulates behavior to conform to social norms. As a result, teens don’t consider risks and they are more impulsive.

Many experts in juvenile crime point to the impulsiveness of the perpetrator who, in 59 percent of the cases, is committing his or her first crime when they are sentenced to life.

“They are not aware of the long-term consequences,” said Gottlieb who has testified at hundreds of hearings to determine whether youths should be treated in the juvenile system.

It is clear that Lewis now believes this, too.

“When I was sentenced to life in prison without the chance of parole, I still didn’t understand the meaning,” said Lewis.

“When we are charged with a crime as a juvenile we are looked at as super-predator, so that when the court’s had started getting tough on crime because of the violation from young juvenile’s. We should be able to have a second chance to have the opportunity to be release from prison to live a normal life. See we change to be more positive and more understand of our action’s and feel bad of what had happen, not all of us but the most of us do regret the thing’s we did when we was younger,” wrote Lewis.

Lewis, who also committed other crimes previous to the convenience store robbery, expressed remorse for his deeds in the correspondence and the desire to undo the death of the store clerk.

“If I was given the opportunity to go back and change anything what would it be? That day the crime that was planned, I would wished I have never met my Co-defendant’s. I would have tooken the bullet for the victim so, that he would die or lost his life for nothing,” wrote Lewis. “And when there is peer pressure the juvenile has no control over what is going to happen and that is because you don’t want to let your friend’s don’t or think your weak.”

But Lancaster County District Attorney, Craig Stedman, feels very differently. He was the assistant district attorney in both Lewis’ and Bourgeois’ cases. He sees the victim’s and the victim’s family’s side of each violent crime.

“Most people know that if you take a gun and shoot someone in the back of the head, it’s wrong,” said Stedman.

He pointed out that the victim is still dead, the family is still suffering, whether he was killed by a juvenile or an adult. Stedman recalled incidents when victim’s family members collapsed in his arms with grief.

Bourgeois was tried as an adult after he and an accomplice, Landon May, murdered Bourgeois’s adoptive mom and her husband. Bourgeois is now spending the rest of his life in prison without the possibility of parole. Incidentally, May and his father, Freeman May, are both on “death row” awaiting execution for completely different murders (the only father/son combination in Pennsylvania).

Although Bourgeois carefully sidesteps discussion of the actual crime and whether or not he is regretful at this point, Stedman clearly remembers the Bourgeois case.

“I can’t describe how horrible this crime was,” said Stedman, although he goes on to do an explicit job of it.

“Michael Bourgeois and his friends were living in a house with a woman, who they had a sexual relationship with, a woman in her 30s. They shot a Mennonite guy in the back of the head when he was riding to work, for fun, they were ramping up their crimes, they were having a great time,” he recalled.

May was the only one charged with shooting the man as he rode to work, but Bourgeois and others were charged with the burglaries.

“They tortured the Smiths to get their pin numbers for their bank account, they thought about it in advance, they talked around the kitchen table, had a summit meeting about it,” said Stedman recalling the much publicized murder of Lancaster County elementary principal, Lucy Smith, and her husband, Terry Smith.

“He (Bourgeois) and Landon May (his accomplice) not only killed Lucy Smith, but May sexually assaulted her,” said Stedman. They hog-tied them with duct tape, hit them with hammers, poked them with barbecue forks for fun, cut them with knives, and shot him (Terry Smith) in the head six times. He didn’t die at first. The bullet rolled around in his skull and this went on for an extended period of time.”

According to the autopsy, among many injuries, Lucy Smith was cut 51 times, shot in the head, beat on the left side of the head with a claw hammer and was sexually assaulted by Landon May.

One of the pair even dropped a television set on Lucy Smith’s head, finally killing her by smothering her.

Steph Herr, a Penn Manor graduate is now a freshman at a local technical college. She was in third grade at Elizabeth Martin Elementary when her principal, Smith, was murdered. She remembers Smith as a positive figure.

“It was a really big shock. I went out and did Book-It [with Smith], I went to Pizza Hut with her and kind of became friends with her in school and then she got murdered,” said Herr. “I was sad, she didn’t deserve to go and she was one of the nicest ladies I ever knew.”

As for Bourgeois’ sentence, Herr finds it just.

“That’s what [Bourgeois] gets because you must be out of your mind to ever kill someone, she didn’t deserve to die. Coming from her son, she didn’t expect that. You would think he would love and respect her. He definitely shouldn’t be walking,” said Herr.

From his prison cell in Hunlock Creek, Pa., a rural area with an estimated population of about 5,585, Bourgeois is eager to talk about everything but details of the crime.

“The Assistant District Attorney (ADA) [Stedman] put the Death Penalty on my plate and I had no idea what to think about it because I was so scared at the time. Just to think about my Life and how all these things led me up to this point. Can you imagine all the thoughts going through my head at this time?…Fortunately the ADA put a Plea Agreement on the table which allowed me to avoid the Death Penalty, but this only meant I was pleading out to 2 Life Sentences,” wrote Bourgeois.

Julia Hall acknowledges there are violent juvenile offenders in Pennsylvania who are violent threats to society and must be kept locked up. But not the vast majority of them, she contends.

Hall has her PhD and is a professor at Drexel University near Philadelphia and is also the Chairman of the Pennsylvania Coalition for the Fair Sentencing of Youth. This coalition is trying to persuade legislators to amend the laws on how juveniles are sentenced, but it’s not as easy as Hall would like.

“Legislators are not very courageous people,” said Hall.

She said legislators are trying to get re-elected, and voting to let a juvenile out early on parole may not be popular with the voting population.

Hall feels that most juveniles who commit crimes would better benefit from some sort of treatment rather then be sent to prison and not ever see the light of day.

David Romano, a local juvenile public defender, is surrounded by youth under the age of 18 everyday who have committed crimes. He agrees with Gottlieb that juveniles are not able to make the decisions and realize the consequences like adults are able.

“There is definitely a difference between a teenage brain and an adult brain,” said Gottlieb, who believes drugs are a big issue and contributing factor to many instances of juvenile crime.

“To suggest that a child as young as 10 can make adult decisions and potentially face adult penalties makes little sense to me,” agreed Romano.

Romano also explained the difference that does exist between sentencing adults and youths.

“The goal of the adult court system is to punish defendants, while the goal of the juvenile court system is to rehabilitate,” said Romano. “I think that the juvenile court system is where these children belong until it’s been proven that they have exhausted all possible resources first.”

A U.S. Supreme Court ruling in May of 2009 seemed to take the same viewpoint as Romano. The court ruled that a sentence of life in prison is “cruel and unusual punishment for juvenile offenders.” The court did make an exception when the crime is murder.

“The pre-frontal cortex of the brain is not fully developed until the mid 20s, (that is the) area that is responsible for decision making, impulse control, delayed gratification…all those things keeping a juvenile from crime. [It’s like] punishing a child because his brain is not developed,” said Hall.

“You’re certainly not the same person at 18 you were at 12, not the same person at 25 or 30. Human beings mature and change. When you put a juvenile in prison for the rest of their life and say they are never going to change, that’s not true,” Hall also said.

According to the Pa. Dept of Corrections, 374 are sentenced as adults and are under 18. The number is lower than the one provided by Hall.

Susan Bensinger, deputy press secretary for the state DOC said it is difficult to get the info on how many prisoners who are serving life terms were charged as juveniles. She said the data base in the department does not allow for easy cross checking.

Hall, on the other hand, claims she is far more careful, and accurate, with the numbers because she contacts every single juvenile who is charged and sentenced as an adult.

Some inmates who were juveniles sentenced to life are now appealing their sentences based on a two-year old U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Roper v. Simmons.

Just like the case of Jordan Brown, who was 11 years old when he allegedly took a hunting rifle and shot his soon-to-be step-mother, who was pregnant at the time, then proceeded to board the school bus. Brown, a resident of Pennsylvania, is charged as an adult and is scheduled to be tried this year.

Hall questions whether a kid Brown’s age has a clear idea of what he is doing during a shooting.

“I show pictures of (Brown) to my class (at Drexel),” said Hall, “They say ‘that’s a little kid.'”

Although it is clear that Michael Bourgeois murdered someone, it is not as clear in Lewis’s case.

Bourgeois, now 27, lives in a 15′ by 8’ cell with another inmate. To pass the time, he watches TV, reads, writes and draws.

“Just the little things in life I miss, like using the bathroom in privacy, eating whenever I feel like it, hanging out with friends, going to different states and see thing sights and just living life freely,” said Bourgeois.

But Bourgeois insists he has changed for the better.

“I flushed my childish ways down the toilet and have grown to be mature and walk proud about who I am,” wrote Bourgeois.

And it isn’t just the juveniles who think they can grow up, mature and become better people

“What do we gain from this?” Hall asked of sentencing juveniles as adults.

Stedman feels that regardless of age, the criminal must pay the consequences for their actions.

“It doesn’t matter to the victim’s family whether they were 17 or 27,” said Stedman.

The price is also a cause for concern. It costs about $1 million to keep a juvenile in prison their entire life. Also, Pennsylvania’s current deficit is $4 billion, $1.8 billion of which goes to the Bureau of Corrections. Pennsylvania’s new governor Tom Corbett has proposed cutting the state’s education budget by $1.2 billion and hiking the allocation to the prison system by 11 percent, which would help fund the construction of new prisons.

When juveniles are sentenced as adults, they are often sent to adult prisons, according to Hall. This is a cause for concern, she said, because it can put the juveniles in danger.

“They are more likely to be raped, assaulted in some way and have very high suicide rates,” said Hall.

According to a 2000 study of juvenile offenders sentenced to life, placement with adult offenders also puts the transferred youth at risk in terms of physical well being. Compared to youth held in juvenile detention centers, youth held in adult jails are more likely to be harmed, including sexual assault, beaten by staff and attacked with a weapon. Suicide rates are also higher among juveniles. These issues surrounding housing adolescents in the same locations as chronic adult offenders have been suggested as possible explanations for recidivism among transferred youth.

There is currently only one juvenile prison in the state, Pine Grove, but most juvenile offenders who are charged as adults end up in adult prisons anyway, according to Hall.

“Someone can rape you or kill you in here and these people don’t care about your life if you live or die,” said Lewis.

Lewis and Bourgeois both say they have devoted themselves to changing their lives around, but not all prisoners share the same motivation as these two.

“I see all these people coming in and out of jail and think that its funny because they are back, so they greet each other with open arms. It doesn’t make me mad, it makes me sad because they have been given a second, third, fourth and even fifth time to be free and they haven’t seen anything wrong with it,” said Bourgeois.

But many, including Stedman and the judges who sentenced them, say that society must be protected from these violent youths.

“The younger people are getting worse than when I started 20 years ago,” said Stedman. “The 17-year-old drug dealer is way worse than the 17-year-old drug dealer from 20 years ago, they are way more frightening. I don’t want to lock people up but people have a right to live crime-free without worrying about someone selling drugs to their children, raping someone, breaking into their homes. Sometimes that means incarceration in state prison. There’s a big difference between someone who raped a 5-year-old kid and someone who stole a piece of paper from CVS.”

At this point the legal system in Pennsylvania agrees with Stedman although Hall said other states are starting to look at juveniles differently these days. But in this state, hundreds of young men probably will never see the light of day.

Click this link to see the number of juvenile offenders with life sentences in each state.

Although they have programs and studies on the inside, the young men who will spend the rest of their lives behind bars still miss things from life on the outside.

“We grow up in here and mature as man, we don’t think the same, we think about the future and family. I lost my family and that is the hardest thing for anyone who grows up in this place, no children, I never been in any real relationship, I don’t know what love is,” Lewis said.

Lewis and Bourgeois feel that they are living proof that people who commit crimes can change and if given a second chance, could walk out of prison a completely changed human being and never again travel down the path of crime.

“I am a strong positive person, and a role model for other young men in here,” said Lewis.

“We can be productive citizens in our communities and loving family members,” said Bourgeois.

Even if Lewis and Bourgeois are correct, they and others will most likely never find out.

Wonderful article! you did a profound job sarah!

Bryan and Sarah,

This is an incredible story. It is well-organized and well-written, but more important than that, it is about a subject that people, especially young men and women our age, need to learn about. This story has the potential to educate readers on a topic that people often overlook, and that is what matters.

I wished you had added Sharon Wiggins, #004371 SCI Muncy, into your research. She has been serving JLWOP since 1971! Originally sentenced to death in 1968 at the age of 17.

Please use your resources and write a letter to the PA Board of Pardons to get her sentenced commuted.

thanks for that important information, it is really helpful. interesting article!http://www.marcabr.net

a young man named Rodney Walton was a co defendant of the clerk who got shot in the neck in lancaster. He was also a lookout, and also recieved life without the possability of parole. Rodney had no idea anyone was gonna die. He was rapped up in peer pressure. I was rodneys celly in SCI Greene. He was 17 at the time. He was one of the most sincere, good hearted people I ever met. He is so talented and a good person. We were cellys for about 7 months back in 98. He was with the wrong crowd, and got screwed. He is a harmless non violent person who is rotting away. FRee Rodney

I really enjoyed reading this story however, everything that Lewis wrote is a lie. He was not outside the store he was inside and he was one of the ones who came up with the idea. He also was the one who carried the gun to the store but handed it off to another defendant. The 2 boys outside were the ones who had no idea what was going on. How do I know this you ask, because Lewis and Gonzalez came to my home and told me what they did. The gun was pulled on me by Lewis because I wouldn’t hide them or the gun at my house.